Navigating stress

Last week’s blog explored stress as ‘overload’ (when things are too much, our capacity to cope becomes diminished). It also considered how our own perceptions shape stress: one person’s stressor may not impact on another person; and how we identify the stressor will impact on how we adapt to it.

In this blog we’ll look at a few things that can help deal with stress in the moment.

Notice your breathing

If you are taking short, quick breaths, then make a conscious effort to slow your breathing down.

One technique for this is called box-breathing:

- As you breathe in – through your nose – count from 1 to 4

- Hold your breath as you count from 1 to 4

- Breathe out – through your mouth – counting from 1 to 4

- Hold your breath as you count from 1 to 4

- Repeat

Research has shown that slow breathing can reduce psychological stress (Birdee et al, 2023) and there’s evidence it can also impact on stress in the body (Hopper et al, 2019), because it lowers our pulse rate and cortisol levels. It’s effectively a way of telling our body to ‘stand down’ from ‘stress’ alert.

On the warpath? Pause and count!

When we are stressed out, we can be on the ‘war path’. We’re focused, determined, angry – and we feel that we need to confront whomever is creating the stress so we can stop it. (This is the ‘fight’ response of stress).

If we can introduce a pause as we march into confrontation, in this pause we can ask ourselves:

- Is this confrontation worth it? Will I achieve what I set out to achieve (if I am having this argument/conversation from a place of stress)?

Something to consider here: if we are trying to control someone else, it’s probably not going to work. Or at least it’s not going to work in the way that we hope. People often recoil when they feel controlled. Forcing compliance can generate resentment.

From the perspective of parenting, Dr Naomi Fisher and Eliza Fricker (2024) argue being in control of our children has become ingrained as a model of good parenting. This can look like enforcement of roles, ensuring behavioural conformity, and sweating the small stuff like getting children to look smart, sit still, and eat properly. However, they highlight that many studies show that the impact of removing choices is that children become demotivated, and some exhibit children downright resistance. This is tough because as they point out, what ‘good parenting’ looks like is based on social pressure. So where children do not adhere to how they are expected to behave, it can feel like the whole weight of societal judgment comes crashing down on the parent. Their book When the Naughty Step Makes Things Worse (2024) works through an alternative model of parenting by eliciting the child’s consent and recognizing children’s agency. They challenge the weight of social pressure (whilst acknowledging it is hard to do so). Returning to our confrontation then, we might feel that we are ‘socially obliged’ to confront our children to set things right and avoid being judged. Stress emerges where we feel the weight of social judgment and we judge ourselves as ‘bad parents’ because of it. But will confronting and/or disciplining our children from a place of stress get us where we want to go? This is where a pause can be important to downgrade from ‘warpath’ to ‘standby’. A good way to do this is firstly to recognise ‘Uh-oh, I’m on the warpath!’ and then count. This could be from 1-10. Maybe it’s 1-100 if we are feeling especially stressed and angry. But this counting gives you that pause to enable you to take a perspective on your situation.

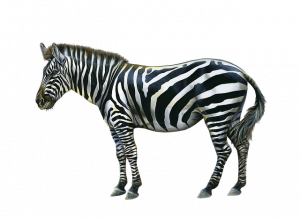

Think like a Zebra!

“What?” I hear you say. Bear with me. Sapolsky’s book Why Zebras Don’t get Ulcers points out that for Zebras stress responses come from immediate environmental circumstances – the sight of a lion in the distance, running for its life, hiding from said hungry lion. Zebras don’t get stressed about things that they anticipate, or social circumstances. In humans the stress response has evolved to encompass social and psychological elements. Sapolsky’s point is that if we look at what is stressing us out, and then ‘think like a Zebra’, we’ll recognise the role of social and psychological perception in creating our stressors. It doesn’t make these stressors go away, but it creates another pause. Another key point he makes is that animals (including humans) experience stress as a short-term crisis, if we experience this long-term stress can make us sick (hence the titular ulcers – more on this soon). Thus, there’s something important here in ‘thinking like a Zebra’ and recognising the ‘in the moment’ quality of our experience: trying not to get sucked into the past (ruminating), or the future (anticipating) and piling on more stress. To be ‘in the present’ is to recognize that this is happening ‘now’ but not necessarily ‘forever’: tempers may be heightened now, or things may feel stressful now, but it will pass, it is not ‘everything’.

If you are stressed and you would like emotional support, please reach out to us at info@careforyoucoaching.co.uk. We support you to support your families.