Navigating Chronic stress or how to survive Survival mode

Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve looked at stress and stress responses in the moment. This blog looks at what happens when stress becomes part of the fabric of our everyday life.

In situations extreme stress the brain’s amygdala senses threat and takes over, initiating a whole-body automatic nervous system response (Van der Kolk, 2014). Our Zebra from last week, running away from a lion, will have this huge stress response whilst fleeing, with the nervous system kicking in to protect the Zebra from threat. However, Sapolsky points out that Zebras can regulate this threat efficiently. Once the lion is out of sight and the threat has dissipated, the Zebra will quickly return to grazing and a normal state (homeostasis). In humans the threat response is not always so easily resolved. For Sapolsky, whilst Zebras are only upset about acute physical crises, humans have a psychology that multiplies and sustains our stressors. And if recovery is unresolved, then the body is unable to return to its normal state. Living in a state of threat in the long-term is ‘survival mode’.

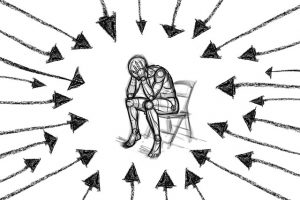

Kastrinos (2021) describes that for carers, dealing with multiple/immense daily stressors, ‘survival mode’ is an adaptive state of ‘trying to get by’. In ‘survival mode’ the body in a defensive state, secreting stress hormones so the person is constantly reacting to danger.

Survival mode for carers might look like:

- Heighted vigilance (feeling like there is a threat constantly)

- Social isolation (‘hunkering down’ and focusing on the person being cared for)

- Prioritising caring for the other person over the carer’s own needs

- Living moment-by-moment – not thinking long term so much as ‘getting through’ the day and ‘surviving’

- Focus zooms in to what is going on ‘right now’ – it’s hard to concentrate, its hard to remember stuff

- Tiny stressors, because they come on top of everything else, feel overwhelming

- Extreme tiredness

People describe this as surviving not living. Whilst this is a psychological state it is also a physical one. Long-term stress and adversity create biological impacts. Lupien et al (2018) describe this as a domino effect, where the long-term release of stress hormones dysregulates independent biological systems (cardiac, immune, metabolic, neurological), creating illness. Yet often these caring obligations are unmovable, so what can be done to relieve stress in these circumstances?

Below are some ideas (not an exhaustive list!)

Sleep

Whilst stress can impact on the quality of sleep, creating the conditions for us to have good sleep means that we can more effectively cope with stress. To help us get better sleep (see Abbo Bacia (2024)) we can:

- Make a bedtime routine relaxing to help you ‘wind down’ and get ready for sleep. Examples might include any of the following: limit blue light exposure, use relaxation or mindfulness techniques if you know them, read a book, listen to relaxing music, avoid stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine, don’t eat too close to bedtime.

- Create a consistent bedtime routine, so we are training our body to be ready for sleep. (This also means going to sleep and waking up at the same time each day)

- Create a good sleep environment: make sure your sleeping space is dark and not too hot, and preferably quiet (ear plugs can help here)

According to the NHS it’s best not to force sleep. If you can’t sleep then get up and do something relaxing until you feel sleepy.

Social support

Social support is an important buffer in reducing the impact of chronic stress for carers (George et al, 2020). Social support helps because it can provide carers with a way to share or offload some of the demands of caring: this might be practically or emotionally. If survival mode takes us into a withdrawal state, social support shows us that we do not have to do it all alone. This support might look like support groups, it could look like coaching or counselling: where people find social support and perceive it useful, such support significantly reduces carer stress and psychological distress.

Finding your Agency and finding Acceptance

When I use acceptance here I’m borrowing from Hill and Oliver (2019) who say that acceptance means ‘reducing unworkable strategies’. What I’m getting at is, where you can, to take control of the things that you can, and find your agency here. Where there are things that you cannot control, or strategies that are not working, let them go. Acceptance then is about taking positive actions towards improving things, whilst also managing any uncomfortable feelings that might come along with deciding to change something.

Hill and Oliver suggest that we can make lots of decisions where we try to control our environment in ways that ultimately do not help us (‘unworkable strategies’) – we might distract ourselves, ‘opt out’ (hunkering down), adopt unhelpful thinking strategies (e.g. worrying, self-criticism, over-analysing), or even use substances (e.g. food etc.) to help us control things that are difficult. This might work in the short term, but they don’t ultimately help us and can end up reinforcing our stress. Acceptance here would look like asking what we would want to be different, and what alternative ways can we use to get there that are in our control. We can’t control that our child has been refused and EHCP, but we can control how we approach this going forwards (e.g. research, social support).

A final thought on agency. Agency might look different for everyone, but a key thing I have witnessed in talking to carers is it’s so important that you have something for you. This might be a walk, knitting, swimming, something that is yours alone, a space and a time to replenish and reconnect with yourself.

If you think you are in survival mode and you would like support, please reach out to us at info@careforyoucoaching.co.uk. We support you to support your families.